Albert Einstein is the pop culture unicorn of science; the disheveled hair, the calm grin, and the tongue-out photo that singlehandedly licensed nerds to be naughty. Yes, I have the t-shirt... But while physics classes wax poetic about his Theory of Relativity, one thing they don't teach you is that when it came to love, Einstein’s personal life was far from, well, monogamous.

The short answer? He didn’t have the vocabulary, but, dear reader, his lifestyle was practically a case study in consensual non-monogamy (if you squint past the patriarchy and subtract some modern ethics).

Einstein wasn’t shy about his inability (or refusal) to stick to one lover. His romantic exploits were as prolific as his equations: multiple concurrent affairs, emotionally entangled liaisons, and a deeply skeptical view of lifelong monogamy. He famously wrote, “I am sure you know that most men (as well as quite a number of women) are not monogamously endowed by nature.”

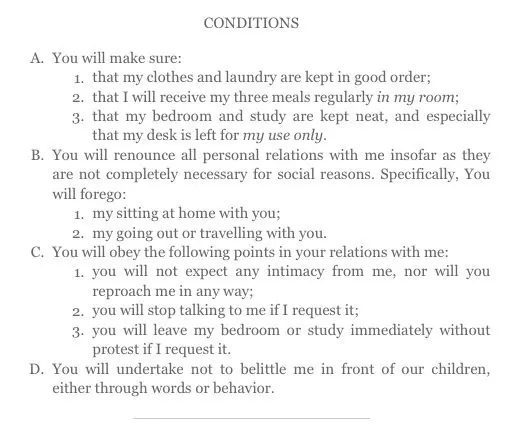

His first marriage to physicist Mileva Marić started with promise; think early 1900s nerd flirtation. However, it disintegrated into disillusionment and negotiation. As the union crumbled, Einstein began an affair with his cousin Elsa Löwenthal. (Yes, cousin. A different headline for a different day.)

Image Source: INTP

Mileva was fully aware of her husband’s habitual side quests. So much so that when they divorced, she crafted a shrewd little clause into the settlement: she’d get the Nobel Prize money he hadn’t yet won. Basically, she got a post-dated check for a decade of emotional labor. Talk about ROI.

Einstein married Elsa in 1919. One might think that marriage number two would foster domestic calm, but Albert Einstein was not a man for tradition. His affairs multiplied like subatomic particles. There was Bette Neumann (his secretary), Margarete Lenbach, Estella Katzenellenbogen, and Ethel Michanowski, to name a few. At least one of these women allegedly followed him from city to city, making it an early prototype of the “situationship.”

And Elsa? She knew. Her tolerance reportedly hinged on public discretion; don’t embarrass the family, and we're good. It was less “I support your journey” and more “don’t let the neighbors gossip.” Polyamorous-by-neglect? Possibly. But still, she didn’t demand fidelity. She negotiated around it. That’s not a traditional marriage… that’s a soft-launch poly contract written on the back of repression.

The word polyamory didn’t exist in Einstein’s lifetime; it first appeared in 1968 when Morning Glory Zell coined the term “polyamorous relationships” in a neopagan context. But Einstein’s letters, the paper trail of his libido, show a man fundamentally at odds with monogamy as a concept.

To a woman asking about her messy love life, he responded:

"Marriage is the unsuccessful attempt to make something lasting out of an incident."

That’s not advice; that’s a mic drop.

And this wasn’t just pillow talk or post-coital rationalizing. Albert Einstein shared these views with friends, family, and even colleagues. He revered his friend Michele Besso’s long monogamous marriage, not because he believed in it, but because he knew he couldn’t do it himself. "An enterprise in which I twice failed rather disgracefully." There's self-awareness. There's also a wink of relief.

What makes Einstein different from your average philandering academic? Blunt honesty. He told his wives about his lovers. He wrote home about them. He identified the tension between human biology and societal rules; not to excuse himself, but to articulate a broader truth.

In the U.S., Einstein went from "suspicious Jewish pacifist" to "grandfatherly cosmic thinker" in record time. His love life should’ve tanked his image, especially given the era's obsession with wholesome nuclear families. Instead, Americans mythologized the mad genius who just couldn’t tie his shoes or his relationships.

Even J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI amassed a 1,400-page file on him. The agency treated his romantic ties as national security threats. But the press? They kept his secrets. When newspapers did reference his companions, they were often labeled “assistants” or “family friends” rather than lovers.

By the modern definition, ethical, consensual non-monogamy fueled by respect rather than deceit, Einstein was more proto-poly than pride parade-ready. His relationships leaned on transparency, not secrecy; on resisting social norms, not conforming to them. But he didn’t operate within a community or code of conduct like today’s ENM circles. His relational ethics were undisciplined and tinged with ego and power structures, as with most men of his station.

And yet, the underlying philosophy that monogamy is a biological fiction, that connection can’t be caged, places him eerily close to modern poly theory. He wasn't cheating. He was philosophizing. In letters, in marriages, in mistresses; he wasn't just living outside the box, he was busy inventing relativity inside a triangular one.

We may never know if Einstein would’ve called himself polyamorous had that language existed. But we do know he rejected monogamy, practiced open dynamics (however asymmetrically), and viewed fidelity as a social construct rather than a biological imperative.

He wasn’t a role model. But he was a blueprint: flawed, famous, and fervently uninterested in pretending to be someone he wasn’t. He brought that same renegade spirit to his relationships as he did to space-time. And for that, dear reader, he may not be a gold-star polyamorous icon, but he makes one hell of a conversation starter in your next group date.